Today, everyone has been talking (with good reason) of the foiled terror plot in Britain.

I have nothing to add. If you want information see Michelle Malkin or Charles Johnson for roundups, links and commentary.

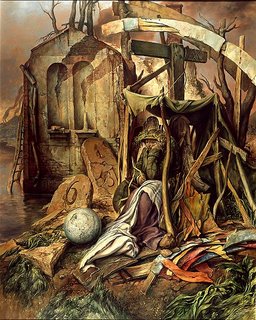

With the president of Iran making repeated existential threats towards Israel, and the Jihadis' view of the US as the Great Satan to Israel's little satan, I would like to bring your attention to the artist Samuel Bak.

Bak has been an artistic hero of mine since I first ran across his work at Pucker Gallery almost fifteen years ago. His work is intensely spiritual, and revolves around his Jewish heritage and his survival of the Shoah (the Holocaust). He was only eleven at the end, when the Soviets liberated the 200 survivors of the 70 - 80,000 Jews that had been in Vilna before the Nazis came. Now he lives and paints in Boston.

(images and text from the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies)

Now to a few thoughts about my "ongoing journey" through the difficult terrain of art that stems from, and relates to, the Holocaust. Years ago, when my art had reached something of its present form, I was nonetheless plagued by an incessant feeling of contradictions and shied away from admitting a direct connection with the Holocaust.

I feared that a Holocaust-related interpretation would narrow the meaning of my work. After all, I am trying to express a universal discomfort about our human condition, and the experience of the Holocaust, which sheds such a cruel light on the entire catalogue of human behavior, is specific, despite the vastness of its lesson. Wouldn't it become a factor of limitation? Being a survivor, I was familiar with the world's reluctance to listen to our harrowing stories. People needed time to study the Shoah and to grasp all its implications.

This reluctance to expose ancient wounds might also come from a fear of being thought to solicit commiseration. We live in a society that hungers for sentiment – worse, sentimentality. And sentimentality perverts truth. Furthermore, most of the art that I then encountered on this theme, art produced in the sixties and seventies, was to my eyes less than acceptable. Surely, some powerful works must already have existed, but I was unfamiliar with them.

Fortunately, the situation has changed. At present, the challenge of anchoring art in meaningful themes does not scare away talented artists. And the present conference is proof of a substantial change of attitude.

In 1978 a retrospective of my work was planned to take several years and to travel through a number of German museums. I was torn between two opposing feelings: my willingness to grant permission to show the work, and my reluctance, or rather my total unwillingness, to bring myself to revisit Germany. I never made it to Heidelberg's museum to attend my show's debut, and it took me months to decide to come to the festive opening in Nuremberg in the German National Museum. Nuremberg, a city in which the ghosts of my murdered father, grandparents and decimated family clung to me with an uncanny force. It wasn't an easy task, but this time I made it!

The day after the opening, when revisiting my show and stumbling on a visit of high school youngsters, I learned something of value. Listening to a capable instructor and to the young people's interaction with him, I understood how important it had been to bring my art to that place. I was witness to a process of their coming to terms with a terrible past. It was a courageous course. Not too many people in other European countries have been up to it. Suddenly, letting my work be seen explicitly in the context of the Holocaust made a lot of sense. To my personal view the walls of the German National Museum transformed my paintings, and I realized that my artistic choices "worked."

As you have seen, my work refrains from imagery that is overly explicit. Everything in it is transposed to a realm of imagination. This transposition must have echoed in the souls of the young Germans to whom -- as I have described -- it gave access to a past that was loaded with guilt. To a painter who creates in the solitude of his studio, such an expression of solidarity is a blessing.

What an irony, and at the same time what an emblem of the extremes of human behavior –and yet also of coming to terms, of accepting change, even, if you wish, of redemption. (speaking, I believe, of the cross in the painting)

The Jewish People faced one genocidal threat in the last century from a tyrannical philosophy bent at dominating the world. Now we have the Mad Mullahs and the Jihadis.

Mark Twain said "The past does not repeat itself, but it rhymes."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home